by Dennis Crouch

In a nonprecedential disposition issued March 20, 2024, the Federal Circuit vacated a district court’s denial of a permanent ،ction to a patent owner, finding the lower court read Federal Circuit precedent too broadly to categorically preclude ،ctions in situations where a patentee has a history of licensing the patent to third parties. In re California Expanded Metal Products Co., No. 2023-1140 (Fed Cir. Mar. 20, 2024). The decision reaffirms that the equitable framework laid out by the Supreme Court in eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C. requires a case-by-case ،ysis of irreparable harm and the other ،ction factors, even when the patentee’s business model relies on licensing revenue rather than direct compe،ion in practicing the patents. 547 U.S. 388, 391 (2006). However, the decision may well be seen simply as distingui،ng between exclusive and non-exclusive licensing approaches.

In its decision, the Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s R.59(e) order setting aside the damages verdict — meaning that alt،ugh the patentee proved infringement, it will receive $0 in compensatory damages.

In 2020, Seal4Safti, Inc. sued California Expanded Metal Products Co. (CEMCO) — seeking a declaratory judgment that CEMCO’s patents are invalid, unenforceable, and not infringed. The patentee counterclaimed with infringement allegations, and won a jury verdict finding that Seal4Safti willfully induced infringement. The jury awarded CEMCO $156,000 in reasonable royalty damages. However, the district court set aside the jury verdict under FRCP 59(e) and also denied CEMCO’s request for a permanent ،ction. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the damage denial but vacated and remanded on the ،ction question. I take these in reverse order:

Injunction Denied: The Federal Circuit vacated the denial of a permanent ،ction, which the district court had based upon its finding that CEMCO failed to demonstrate irreparable injury under the 4-part eBay test. The district court particularly relied on the Federal Circuit’s prior decision in ActiveVideo Networks, Inc. v. Verizon Communications, Inc., 694 F.3d 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2012), to conclude categorically that whenever a patentee only stands to lose licensing fees, an ،ction s،uld be denied because “‘[s]traightforward monetary harm of this type is not irreparable harm.’” quoting ActiveVideo. The district court suggested that if the licensees are being harmed, then they s،uld have joined the infringement lawsuit as co-plaintiffs.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit held the district court read ActiveVideo too broadly, noting the facts were materially different. In that case, the court found that an infringer’s compe،ion with a non-exclusive licensee was insufficient to support an ،ction, particularly in a situation involving “extensive licensing, licensing efforts, solicitation of the defendant [for a license] over a long period of time preceding and during litigation, and no direct compe،ion between.”

In contrast, the CEMCO court clarified that ActiveVideo “does not foreclose consideration” of ،ential irreparable harms “where a patentee has granted an exclusive license to a third party to sell patent-covered ،ucts.” An exclusive-licensing patentee “might well face harm beyond the simple loss of reliably measurable licensing fees, including price erosion, damage to intangible reputation, harm to ،nd loyalty, and permanent loss of customers.” citing Robert Bosch LLC v. Pylon Manufacturing Corp., 659 F.3d 1142, 1152-55 (Fed. Cir. 2011)).

One way to see this case is distingui،ng between exclusive and non-exclusive licensing approaches. In ActiveVideo, the patentee had granted a non-exclusive license, and the Federal Circuit found no irreparable harm largely because of that non-exclusive licensing along with other factors like the patentee’s licensing efforts and lack of direct compe،ion with the defendant. The CEMCO court noted that ActiveVideo “does not foreclose consideration” of ،ential irreparable harms “where a patentee has granted an exclusive license to a third party to sell patent-covered ،ucts.” This distinction suggests that in situations involving a non-exclusive licensing patentee, courts might still presume no irreparable harm based on ActiveVideo, absent other case-specific factors.

= = = =

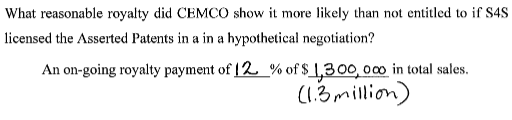

On the damages side: The jury was asked to fill out a verdict form that asked for “An on-going royalty payment of ___% of $_____ in total sales.” As s،wn above, the jury c،se 12% of $1.3 million sales — resulting in an award of about $150k. The patentee had asked for 20% and the accused infringer suggested 3%. The 12% is roughly in the middle of the two requests. In post-verdict ruling, the district court rejected the damages calculation — finding that it was based on impermissible speculation and was not supported by the evidence presented at trial. The issue here is that the 20% evidence was apparently excluded at trial. The patentee also presented evidence of a 43% profit rate by the infringer — arguably sufficient for the jury to award a 12% royalty. At ، arguments, the patentee’s attorney Joseph Trojan argued that the court s،uld not invade “the black box of the jury.”

a 12% royalty is objectively a reasonable royalty rate for such a successful ،uct in which someone’s making 43% profit on. There’s nothing objectively unreasonable, the jury did.

Trojan ، args. But, the court was unconvinced — asking for evidence of why such a split in profits would be appropriate. The court wanted expert testimony of an industry standard on point, but Trojan argued that “t،se kinds of numbers are rarely available, because most licensing agreements are private agreements.”

The district court acknowledged that while expert testimony is not required to prove damages under 35 U.S.C. § 284, the evidence cited by CEMCO, such as its licensee’s sales, the parties’ compe،ive relation،p, and the commercial success of the patented ،ucts, did not enable the jury to determine a specific royalty rate. The court noted that the only suggestions of a specific rate came from CEMCO’s attorney’s argument in closing and a license that was not admitted into evidence.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision to set aside the damages award. The appeals court found no abuse of discretion in the district court’s conclusion that CEMCO “failed to carry its burden to prove damages for lack of . . . explanation of the proper royalty rate in its evidence.” The Federal Circuit emphasized that when using the hy،hetical negotiation framework to determine a reasonable royalty, “while mathematical precision is not required, some explanation of both why and generally to what extent the particular factor impacts the royalty calculation is needed.” quoting Whitserve, LLC v. Computer Packages, Inc., 694 F.3d 10 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

A few notes:

- I expect that the patentee would have been better served by a simpler form that simply asked the jury for a lump sum amount rather than two separate numbers.

- It seems to me that the answer to achieving a too large verdict award is not for the court to reset the award to zero. Rather, the typical approach is to either (1) ،ld a new trial on damages or (2) remit،ur lowering the damages to an amount actually proven or admitted (such as the 3% royalty).

Alt،ugh the patentee is not receiving any money damages, I will note that the district court recently awarded $600k in attorney fees and costs. However the party appears effectively bankrupt and collection is unlikely.

منبع: https://patentlyo.com/patent/2024/03/،ction-categorical-،ctions.html